Recently, there has been growing interest in translation studies. What could be the reason behind the rapid rise in the popularity of translations across the globe? It is often said that the gap between developed and developing countries boils down to knowledge and is rooted in educational institutions.

In debates about education, the role of language has always been fundamental. One key question frequently raised in discussions on teaching and learning is: what should be the medium of instruction?

Immediately after independence, Urdu was given the status of the national language and English the status of the official language. Since Urdu had become a part of Muslim identity during the Pakistan Movement, it was declared the national language. The very first education conference held in 1947 also discussed the medium of instruction and the status of Urdu.

The 1959 Sharif Commission recommended that Urdu should become the official language within 15 years. This process was expected to be completed by 1974. However, the 1973 Constitution extended this period by another ten years. Despite a lot of lip service to Urdu, no real steps have been taken for its promotion and development.

Entry into the most important civil and military bureaucracies, for example, requires proficiency not in Urdu but in English. Similarly, for jobs in multinational companies in Pakistan, knowledge of English is essential. As a result, compared to English, Urdu—the national language—never became the first choice for people socially. Instead, English became the language of power; its mastery could open doors to employment and was seen as a mark of high status in society.

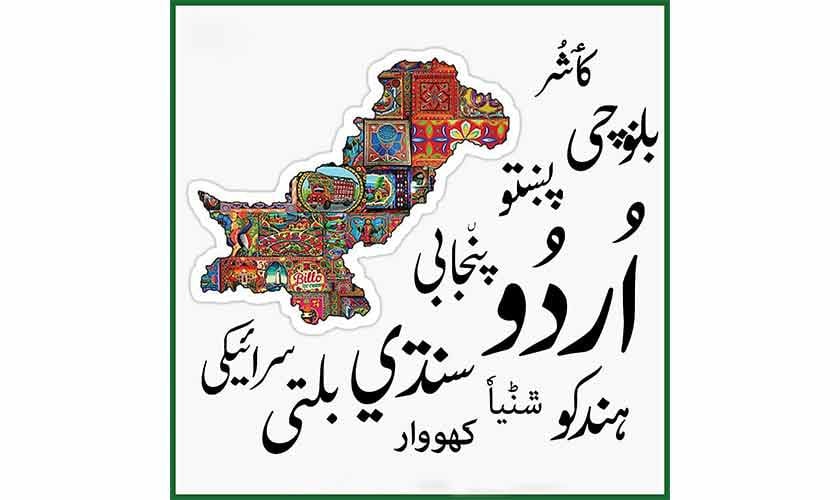

Another key responsibility ignored at the government level was the promotion of Urdu alongside other Pakistani languages. Over time, the social and economic gap between the rich and the common people widened, and language played a crucial role in this divide. English, accessible to only a small segment of society, became the language of the wealthy, while most people, unfamiliar with English, were excluded from modern education and knowledge.

Throughout Islamic history, translation bureaus were established at the state level to quickly translate books published in other languages. In modern times, the translation bureau of Hyderabad Deccan continued this proud tradition. Had Pakistan maintained this tradition by creating an effective translation bureau—translating books and articles from other languages—the goal of making Urdu the medium of instruction may have progressed beyond a mere political slogan.

Currently, only about six percent of Pakistan’s population has access to English books and journals, meaning the majority cannot reach the information contained in English research articles and publications. To bridge social and economic divides, access to knowledge in English and other languages is vital. Therefore, establishing a national translation bureau is essential.

If managed by the Higher Education Commission (HEC), nearly 200 universities can be included in this effort. However, a project of such magnitude will face several challenges.

First, the rapid pace and scale of knowledge and research advancement mean that books and articles are being published constantly. The spread of knowledge cannot be matched by sporadic translation efforts. To meet the objectives, translation efforts must be scaled up and coordinated.

Second, choosing which books to translate is critical. A committee of subject matter experts should be formed to recommend important works for translation. Securing copyrights for these books is also crucial and can best be handled at the government level.

Third, to ensure accuracy and reliability, each translation must undergo thorough review and verification, possibly with assistance from an existing government institution.

Fourth, technology should be employed to address challenges related to scale and frequency. This will require collaboration with leading IT institutions. However, machine-facilitated translation is currently only about 70 percent accurate. To improve and sustain quality, a team of human supervisors is essential.

Translator training can be supported through short-term courses. Additionally, a directory of translators should be compiled for easy access. To foster a translation culture, universities should be encouraged to establish Translation Studies departments, and existing departments should receive support.

Following a successful translation, publication is the next step. Digital copies should be uploaded to the HEC Repository for online access. Support can also be sought from the National Book Foundation for physical publications, given its focus on expanding students’ access to books.

Successful implementation of this plan will require coordination across several institutions. If the Higher Education Commission takes the lead, along with participation from leading universities, the Ministry of Education, and the National Book Foundation, this vision can become a reality—opening the doors of knowledge to those who cannot access English or other first-publication languages.

It is also important to note the need to translate from Urdu and other Pakistani languages into national as well as foreign languages, thereby promoting linguistic diversity and cultural exchange on both national and international levels.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1348327-translation-education-and-development