Subjective silence itself is not emptiness. It is attention and receptivity. It is also a light, for the soul is ordered to objective silence, to great mysteries in which we participate.

> “And as we talked and panted for [eternal wisdom], we touched just the edge of it by the utmost leap of our hearts; then, sighing and unsatisfied, we left the first-fruits of our spirit captive there, and returned to the noise of articulate speech, where a word has beginning and end.”

> —St. Augustine[1]

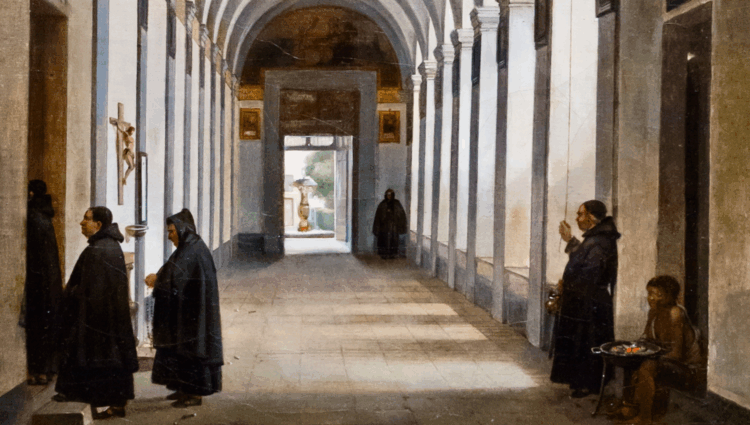

I vividly remember my first visit to the Benedictine abbey of Notre Dame de Fontgombault in France. I had been told that Fontgombault had ancient, beautiful buildings, but as that information had not entered my imagination, I was surprised as the taxi pulled alongside the ten-foot stone wall that enclosed the abbey grounds and then drove around to the grand portal of the twelfth-century abbey church.

My three companions and I went in and were instantly captivated by a place drenched with centuries of prayer and silence, vaulted high and arched, shadowed in mystery. We arrived just in time for Vespers and sat down in the front row. The stillness of the place enveloped us.

Suddenly, a monk appeared in the sanctuary and grasped a rope that reached all the way up to the lofty bell tower. He began pulling the rope, and we heard the calm sound of a bell ringing regularly and slowly: bong . . . bong . . . bong. A long line of eighty monks entered the sanctuary two-by-two, serenely, graciously.

The bell eventually stopped, the monks knelt for a moment, and then, all together in one movement, quietly got to their feet. Next, rising out of the silence, I heard for the first time a single voice chant: “Deus, in adjutorium meum intende.” Eighty voices responded: “Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina.” Then the psalmody began.

Here were men accomplishing what is essential for human life, praising God, unperturbed by the tumult of the world. I especially remember the refrain of Psalm 136 jumping out at me, echoing in my heart: “For His merciful love endures forever.” The silence continued to underlie the singing of the calm, simple, attractive Gregorian melody. At the end, when the singing was over, the silence had become palpable, enriched somehow.

—

Afterwards, we were shown our rooms. In mine, I found on the wall a little engraving of the Blessed Virgin holding a finger to her lips; it was titled Notre Dame du silence—“Our Lady of Silence.” The title intrigued me, and it still does.

Soon, we were ushered to dinner in the monks’ refectory. Things remained quiet, with the monks in service smoothly accomplishing their tasks, and the only vocal sound being that of a monk reading out loud from the life of a saint.

Lastly, we experienced the serenity of Compline in the dark church, lit by only a couple of lamps. At the end of the office, a monk lit also two candles in front of a statue of Our Lady, and the monks sang the Salve Regina to her. When the last words had been sung, a bell peacefully sounded again in the silence, this time for the Angelus. Then all was quiet for the night, as if all the singing and praying had been building up to that silence.

I tiptoed up to my room; it felt like the whole monastery was dripping with a silent presence. I remember hearing the church bell ringing the hours during the night, rising out of the silence then fading back into it. This only increased the feeling of a dense presence.

That was my first experience with silence, you might say. I entered Fontgombault a year later in order to enter more deeply into that mystery. Twenty-five years later, Fontgombault began our monastery here in Oklahoma, Our Lady of Clear Creek.

—

There were two silences in my experience that first evening at Fontgombault. The first was the monks’ attention, which I am going to call here subjective silence. The second was what they were attentive to—an objective silence, one might say. Singing the psalms, ringing the bells in that magnificent church, all was ordered to a contact with God’s mysterious presence.

Subjective silence, an attentive receptivity, is essential for a truly human life. To observe events, to listen to a lecture, to read a book, to speak with a friend, we must not be distracted by noise—especially by interior noise—that is, extraneous preoccupations and wayward imaginings. We need to cultivate a certain interior calm beyond the hubbub of superficial impressions and drives if we are going to really reflect, make personal decisions, and be able also to give ourselves to others instead of blindly following egotistical impulsions.

We need an interior place of silence to receive Our Lord’s word. Entering into objective silence is the main purpose of the subjective one. We need to recollect our faculties around more important thoughts in order to be attentive to what really counts in life.

Now, what really counts in life are mysteries, such as friendship, love, beauty, and, most of all, God. A mystery is not merely something that we have not figured out. Rather, it is something we do know but only obscurely and will never get to the bottom of. Knowledge of mystery is like being plunged into the ocean: the mystery penetrates us, surrounds us; we know we are in it, but we cannot embrace it all. Mysteries are thus imbued with a sort of silence, something beyond our clear knowledge.

Msgr. Romano Guardini stresses the importance of interior silence to hear the objective one:

> “Silence or stillness is the tranquility of our inner life, the quiet at the depths of its hidden stream. It is a recollected, total presence, where one is all there, receptive, alert, ready. It comes only if seriously, earnestly desired. We must be willing to give something in order to establish a quiet area of attentiveness in which the beautiful and the truly important reign. Once we have experienced it, we will be astounded that we were able to live without it.”[2]

He speaks of beauty and truth. By Christian revelation, we know even more tremendous mysteries: the incarnation of Our Lord, the Redemption, His presence in the Holy Eucharist, the Church, Our Lady, and most of all, the ultimate mystery, infinitely greater than all created mysteries, than the entire universe—that of the Most Holy Trinity.

To participate in the silence of the Blessed Trinity is the ultimate goal of our interior silence, as St. John of the Cross intimates in a famous text:

> “The Father spoke one Word, which was his Son, and this Word he speaks always in eternal silence, and in silence must it be heard by the soul.”[3]

During the course of this book, we will try to understand better what St. John is saying here.

—

Subjective silence itself is not emptiness. It is attention and receptivity. It is also a light, for the soul is ordered to objective silence, to great mysteries in which we participate. Cultivating interior silence consists, firstly, in taking away obstacles that distract our attention from that light. Secondly, we enrich this interior silence with all we have learned that attunes us to the mysteries. For example, we learn about the mystery of beauty, we acquire a sense of it, and become able to enter into it. Ultimately, our understanding of beauty points us toward God’s inconceivable Beauty.

The epigraph of this introduction evoked the two silences and the path from one to the other. Concerning his famous ecstasy at Ostia with his mother, Monica, St. Augustine described how, through a meditation, the two rose to a great concentration and contact with God’s eternal Mystery, His Silence. The meditation, like the meditation of the psalms, by the Fontgombault monks and the praying of the psalms, caused a certain enriching that attuned to the great object.

We monks enter the monastery to cultivate interior silence in order to participate better in God’s silence. Not only monks, but everyone must make space in themselves to give place to God.

A deep, rich silence, receptive to truth, goodness, and beauty, has never been easy. But special reflection and deliberate effort for it are required today, because our world is a culture of noise, both interior and exterior. It fosters diversion from God, from the true meaning of things, and from our authentic selves.

A century ago, it was said that the modern world is a conspiracy against contemplation, against silence. And even two centuries ago, during a time which seems peaceful and silent to us, Søren Kierkegaard describes what corresponds amazingly well to our situation. The world has simply gone further in the same direction:

> Create silence. Ah! everything is noisy; everything in our day, even the most insignificant project, even the most empty communication, is designed merely to jolt the sense or stir up the crowd—noise! And man, this clever fellow, seems to have become sleepless in order to invent ever new instruments to increase noise, to spread noise and insignificance with the greatest possible haste and on the greatest possible scale.

> Everything is turned upside down. Communication is brought to its lowest point with regard to meaning, and simultaneously the means of communication are brought to their highest with regard to speed and overall circulation. O! create silence![4]

—

I invite the reader to join in the adventure of silence. I propose that we make a pilgrimage together to the Sanctuary of Silence, where Our Lord dwells. I have called this book *From Silence to Silence*—that is, establishing interior silence and then proceeding toward contact with God’s silence.

I will begin with considerations on how to cultivate the first silence: an interior, receptive calm. Then we will be ready for a second stage, in which we will meditate on some mysteries that advance us toward God’s infinite and silent mystery. Lastly, we will try to see how we can reach His silence through the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity, which ultimately means through prayer.

In the text above, Augustine referred to normal speech as noise in comparison with God’s transcendent silence. The dictionary defines noise as an unpleasant or undesired sound, as an annoying, irregular one. Noise, for us in this book, will be whatever is disharmonious with our deep life, whatever at some level impairs our attention to great truths, and, in the last analysis, anything that hampers our progress toward God.

We will keep in mind Our Lord’s silence. During His earthly life, in the bottom of His soul, He was in silent communion with His Father. He spent most of that life in the quiet home of Nazareth, began His public life with the silence of the desert, and even during those three years of preaching would regularly sneak off to be alone with the Father. He was mostly silent during His passion. Finally, He returned to the silence of the Father.

We will also think of Mary’s silence when she bore Jesus in her womb and waited to see His face, of her adoring silence at Bethlehem, the silence of the separation during Jesus’s public career, her silent pondering of her son’s words and the events around Him, the awful silence at the cross, the silence of Holy Saturday in a calm expectation of her son’s resurrection, and then after the Ascension, the silent waiting in her heart for Him to come to take her.

—

I subtitled this book *A Benedictine Pilgrimage to God’s Sanctuary*. I have not, in view of this book, done research on the Benedictine tradition concerning silence, nor will I particularly comment on the Rule of St. Benedict. I simply put forward my meditations, the fruit of almost half a century of Benedictine life. I have been formed in the great Solesmes tradition, especially through Dom Paul Delatte’s writings and through my master of novices and later abbot, Dom Antoine Forgeot, to whom I will often refer in these pages.[5]

I address primarily the lay faithful and families, but I hope that priests and those of the consecrated life, especially contemplatives, will be able to find some nourishment in this writing. My reflections mainly aim at fostering our life of prayer.

I am not on the summit next to the sanctuary, beckoning to those below; I am, rather, on the slope with the others, striving to put one foot forward at a time. I have, nevertheless, thought deeply and at length on what I write here, and hopefully, have put it to the test in my life.

Let us ask Our Lady to show us the way and accompany us on our journey. Let us also pray to St. Joseph, that man who silently served his two beloved companions. I entrust this work especially to the prayers of that other man of silence, our Blessed Father St. Benedict.

—

Published with gracious permission from TAN Books and the author from *From Silence to Silence: A Benedictine Pilgrimage to God’s Sanctuary* (pp. 12–18), by Fr. Francis Bethel, OSB (Kindle Edition).

Notes:

[1] St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. Mary Boulding (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2012), IX, ch. 10, no. 24.

[2] Romano Guardini, Meditations Before Mass, trans. Elinor Briefs (Westminster, Maryland: Newman Press, 1956), 3–4.

[3] St. John of the Cross, “Sayings of Light and Love,” no. 100, in The Collected Works of Saint John of the Cross, trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez (Washington: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1991), 92.

[4] Quoted in The Power of Silence by Robert Cardinal Sarah, trans. Michael Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017), 86. The cardinal’s book is a treasure of wonderful quotations on silence.

[5] Other Benedictine authors I have frequented are St. Bernard, St. Gertrude, Blessed Columba Marmion, Dom Prosper Guéranger, and Lady Abbess Cécile Bruyère.

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2025/11/silence-benedictine-pilgrimage-gods-sanctuary-francis-bethel.html