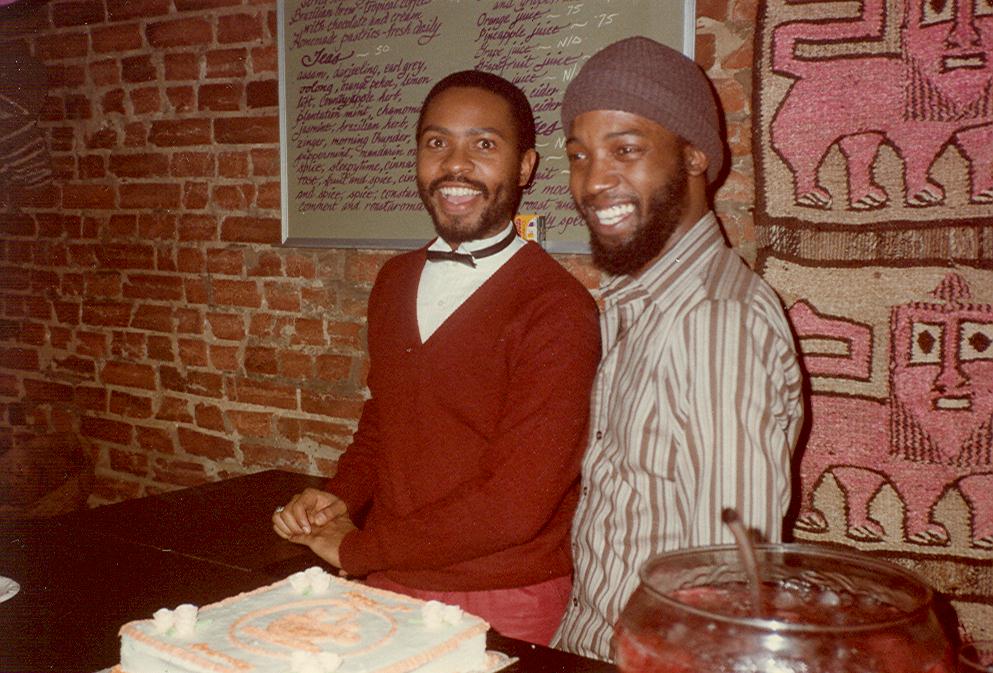

An unassuming two-story brick building in a narrow alley at 816 I St. NE doesn’t wear its earliest history on its sleeve. This alley structure was originally a private stable where residents of the main house up front would store their horse and carriage. There’s no longer a loft door on the upper floor, nor a protruding beam housing a pulley system to hoist hay and horse feed. One owner in the 1980s replaced an exterior facade of original 1891 red bricks with cinder block. Indeed, history isn’t always impeccably preserved, especially in alley buildings that were never intended as homes. David Salter, owner of a stable house in Shaw and author of the blog Preserving DC Stables, loves documenting these structures: “Going through the alleys and looking at these little buildings is sort of like doing an architectural autopsy. You look at bits and pieces and try to fit them together, because once you recognize the elements of a stable, you’ll be able to see the remnants.” With the dawn of the automobile and mass transit, many stables like these, also known as carriage houses, either vanished or assumed alternative-and sometimes off-the-record-uses. Interest in D. C.’s alley buildings has skyrocketed in the past 10 to 15 years, focusing mostly on structures in Shaw, Georgetown, and Capitol Hill that have retained their historic elements. But sometimes history doesn’t remain intact. Instead, it’s transformed by the peculiar tastes and interests of its inhabitants. That’s the case with this 780-square-foot carriage house. In its most important iteration between 1982 and 1989, this was known as ENIKAlley Coffeehouse, named for its location between 8th, 9th, I, and K streets NE. This was a sanctuary, a refuge, and an incubator where Black gay and lesbian artists and activists hosted political and social gatherings, music performances, poetry readings, Kwanzaa dinners, Valentine’s Day brunches, and rehearsals. Inside were exposed brick walls, a fireplace, an upright piano, and a booze-free bar slinging hot teas and juice for 50 cents. Luminaries and upstarts alike made this a home for experimental art. “It was like going into a snowglobe,” recalls local artist Wayson Jones, who worked on a 2021 documentary about the space. “You go through this kind of rough neighborhood paper records list Benjamin as an investor in the Hebrew Free Loan Association of Greater Washington, a committee member for a group supporting Jewish tuberculosis victims, and president of Ezras Israel Congregation of Maryland. To this day, his name is prominent on a metal placard inside Ezras Israel’s synagogue. Just nine months after Futrovsky’s 1929 permit, a classified ad listed the main home and garage for $55 in rent. In 1933, a one-line ad listing homes for rent made sure to mention the “double brick garage and storeroom.” After another long gap in the paper trail, we arrive at the 1980s, when D. C. was a mess of contradictions. Mayor-for-Life Marion Barry was at the helm of Chocolate City and a strong supporter of the arts and of LGBTQIA communities. A local punk scene and dozens of active go-go bands emerged, animating “D. C.’s cultural atmosphere” and “a surge in black pride.” Ronald Reagan’s right-wing agenda led the nation, and “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency” (later renamed Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS) and crack cocaine made the front pages of national newspapers. Up and down the H Street Corridor, the remnants of 1968 riots were still visible. The Atlas Theater was still vacant and would remain so for decades. “Ironically a long period of building stagnation in D. C. (after the 1968 riots) protected many of the remaining stables,” Salter writes in a blog post. Gary Walker, a civil rights activist with a new government job, took a chance on 816 I St. NE despite the boarded-up businesses and homes surrounding it. He could walk to work and wasn’t concerned with being one of the only White people around: “I felt that the only way you’re going to integrate neighborhoods is if you go live in a neighborhood and you integrate it. So I was perfectly happy to live there,” he tells City Paper. He wasn’t alone. Gay men were resurrecting old homes across D. C., making investments in neighborhoods where straight people wouldn’t venture. Walker was charmed by the main home’s multiple entertaining spaces but didn’t have a plan for the rear carriage house. That changed around 1982 when he met and fell in love with Ray Melrose, then head of the D. C. Coalition of Black Gays. Melrose moved in, and Walker was soon connected to a vibrant network of Black queer activists and artists. “It was just a lot of fun,” Walker says. “I lived kind of vicariously through him, because he’s the one who knew all these people in town. He was a real socialite. I would forever meet interesting up-and-coming artists and musicians.” As an interracial couple, Melrose and Walker were keenly aware of the racist practice of “carding” that happened at gay bars across the city. To avoid admitting “African-Americans, women, Latinos, and drag queens,” private clubs would demand multiple forms of identification. “I thought we were one big family, but the White gays were kind of like the straight bars,” says Christopher Prince, a regular fixture at the coffeehouse. “It was the same white supremacy thing but with better clothes. First I’m objectified as a sexual object, now I’m objectified as a criminal.” Out of the need for free meeting and performance space, combined with the realities of carding and the availability of the former stable behind Gary and Ray’s home, the ENIKAlley Coffeehouse was born on New Years Day 1982. For most of the intervening decade, it served as a warm and inviting cultural hub accessible through a derelict narrow alley. Even Prince, a D. C. native, says, “I would go down that alley with the intention of getting behind that steel door as quickly as possible. There was no knocker or doorbell, you literally had to pound on the door. When you crossed that threshold, there was a special place behind that door. Despite the size of the Coffeehouse, which is very small, it was an enormous space to walk into, and that was because of what we were pouring into that building. It was a space of resistance, of organizing, of expression.” Michelle Parkerson, director of the ENIKAlley documentary, described the alley as “pretty debilitated” at the time. “Crack was very heavy in that neighborhood . and you didn’t know what you were gonna encounter,” she says. “But the coffeehouse was very safe.” Parkerson, who was an active member of Sapphire Sapphos, a lesbian support group that used ENIKAlley Coffeehouse as an office, says the booze-free space meant women could bring their children. The coffeehouse hosted singers raising money for demo tapes, choral poetry performances by the group Cinque, jazzy bass guitar, bamboo flute sounds, and more. But regardless of the type of performance, original features of the space always took center stage. An old (and possibly original) fireplace was the sole-and sometimes insufficient-heat source. The second floor still had a large opening from when hay was tossed down from the loft, but Walker and Melrose installed a railing so people could peer down and watch the performances. A room on the second floor (possibly the former coachman’s space) was used to store music equipment, amps, and lights. And as a stand-alone structure built from brick, it was well soundproofed so as not to disturb neighbors. A 1984 Washington Blade article describes a charming scene at a Sapphire Sapphos gathering: “Approximately 20 women sat talking in The Coffeehouse in Northeast Washington one recent Sunday afternoon. About half of them circled two tables in front of a merrily crackling fireplace, while the rest were ranged in chairs along the walls and on stools at the small bar. As one person would pick up the thread of discussion and then pass it on to another, their faces seemed to glow and brighten for a moment, as if their ideas formed a flickering campfire from which they gathered warmth and light.” Prominent poet and activist Essex Hemphill regularly performed at the coffeehouse and directed other performers in rehearsal. A brand-new collection includes his poem “Heavy Breathing” about the brutal murder of Catherine Fuller, whose body was found in an alley garage just one block away from the coffeehouse: “No one hollered STOP! / for Mrs. Fuller, / a Black mother murdered / in an alley near her home . Now is not the time / to be a Black mother / in the ghetto.” The site of Fuller’s 1984 murder was a structure identical to the coffeehouse. Although public records do not identify the precise address, it is most likely a 1891 stable built by Farnham & Chappel and owned by Oella Chappel. By the end of the decade, Walker and Melrose had broken up and performers had moved over to the nearby artist-run d. c. space. Walker eventually sold the house and stable, kicking off a string of three subsequent owners, the first of whom recall seeing a menu still hanging on the wall. “It felt like it was meant for gathering,” says Randy Pumphrey, who co-owned the properties with his sister, Karen, from 1990 to 2013. The stable is currently a rental apartment, and given the housing needs of the District and conversion of similar structures into expensive residential properties, it will likely stay that way for the foreseeable future. The 816 I St. NE carriage house is no museum to 19th-century horse stables, but that might be OK. “People don’t want to live in a museum,” Salter says. “They want to take the bones . wrap it around them, and become something within it that’s different.” Recommended Stories.

https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/774842/on-places-h-street-carriage-house-enik-coffeehouse/